The Terrible Ten were a cool gang of TV Australian kids who rode their own horses around the outback, getting into and out of scrapes with malicious adults. They never seemed to have to go to school or be back home for a deadline. In fact I’m not sure they had homes at all. But then again, someone must have bought their clothes, made them wash their hair and clean those ever bright white TV teeth. In amongst them was a dark haired girl with whom, around my eighth birthday, I became infatuated. I so wished to invite her to my party, show her off to my friends and help her win at blind man’s buff. But to have the slightest chance of competing for her affections with those horse riding, outback savvy boys in the Terrible Ten team, I needed to have something special up my sleeve. Fortunately for me, I was very special. I first secured the attention and admiration of the girl in the Terrible Ten by demonstrating how uniquely special I was. I could fly. And I was the only boy around that could. This special power literally lifted me above the cocky and generally bigger boys of the TT gang. Whilst I swooped, looped and dived in the air above them, they’d gasp and yell ‘whoa look at that kid, how’s he do that?’. My dark-haired girl would just look up at me with a knowing and connecting smile whilst musing ‘Yep I like that boy, he’s brilliant. How cool will it be to have a best friend, a boy friend, who can fly!’.

From that first airborne performance we were inseparable, more than mates. To be fair, the boys of the Terrible Ten didn’t appear to resent me or see me as a freak or alien. Rather they seemed to consider it neat (and perhaps useful) to have a kid who could fly in their gang, even if he did talk strangely and have the skinniest legs. Flying was my ticket to ‘in’. Although once ‘in’ I don’t recall the rest of the Ten actually featuring in our adventures. It was mainly her and me getting into scrapes, tracking and hiding from the disproportionate number of outback villains we chanced across on a daily basis. Very quickly of course, she was able to see beyond my super powers to like and admire me simply for the great and fun person I was. So I stopped flying and became a normal kid, but a kid who’d secured the girl in the Terrible Ten for his special friend and soul mate. A ‘bezzi’ who mysteriously never had a name. We didn’t use names and didn’t need them. But we did hold hands just now and again.

We were having such a great time. Those summer days together were brilliant, and I never went home for tea or had to obey a curfew. I was in charge of my life and she of her’s, and for that innocent and blissful early summer we two were one. Until, one after another, more distracting and irresistible forces bounced their way into my life. These new friends did have names, like football, rugby and cricket. So sadly, albeit inevitably, by ‘eight and a half’ (fractions of years were very important then) I’d forgotten my girl from the Terrible Ten. No fall out, no big statement, no big closure, no scribbled clumsy note, we just grew out of each other and let go. Relationships sometimes go that way. My new ‘bezzi’ was a very real and equally cool maroon track suit, with two statement thin white v’s on the front. My prized 1963 gift from Santa, I was special in that ‘tracky’ and flying whenever inside it. We were inseparable, getting into scrapes chasing and tackling the opposition, scoring last second cup winning goals and hitting Test clinching centuries to the whooping adulation of cheering fans, ‘whoa look at that kid, how’s he do that?’

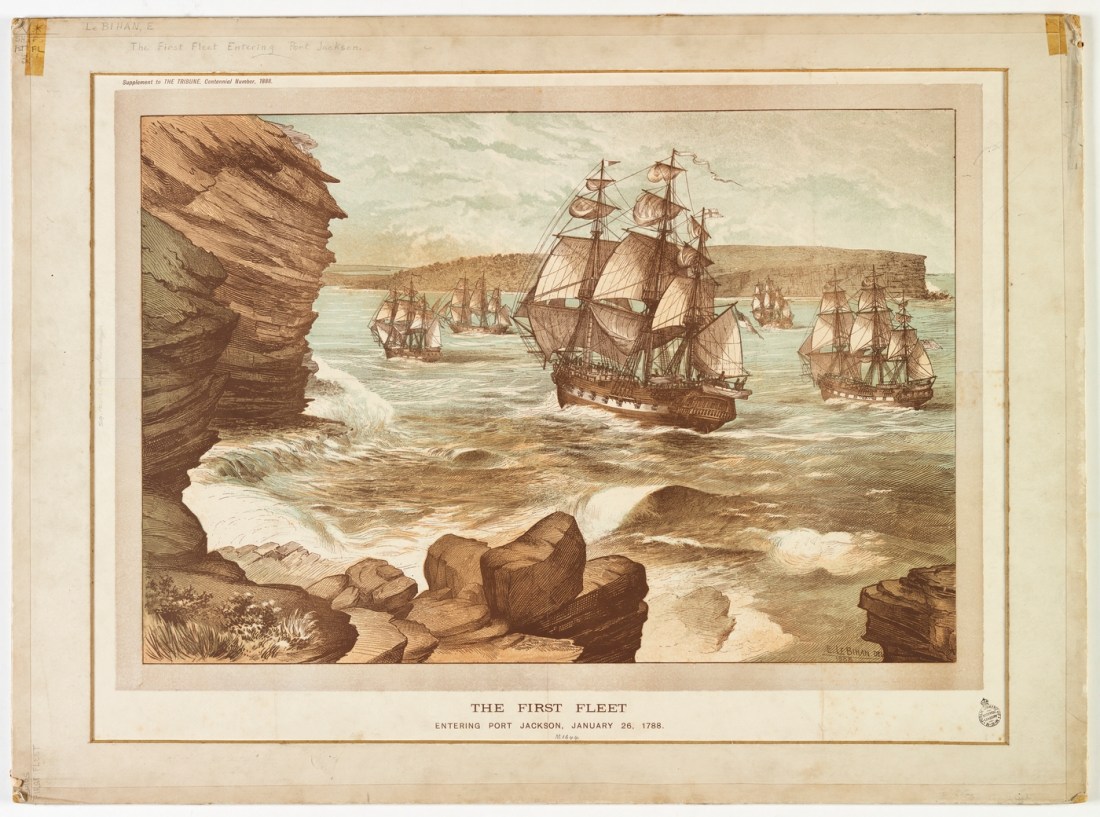

Around 230 years ago aliens landed in Australia. Their impact has not been quite so benign or their presence so easy to dispatch, as that of the infatuated flying kid.

Australia’s isolation over millennia evolved its own unique catalogue of flora and fauna, many cute, many lethal and many both. But all playing their part in a rich, balanced and sustainable ecosystem. Then just over two centuries ago arrived a disruptor. The European. Whilst no doubt many of these new arrivals had laudable intentions and undeniably strong spirit, few understood the fragile equilibrium of the new land on which they were about to feast. Names such as New Holland (for mainland Australia) and New South Wales were early signals of what was in store for this bountiful island and its unsuspecting inhabitants.

Australia has the highest mammal extinction rate in the world. Thirty native mammal species have become extinct since the arrival of Europeans, including the elegant toolache wallaby, the cheeky-chopped broad-faced potoroo and the cute desert rat-kangaroo (or oolacunta). Birds have fared little better. The paradise parrot, black emu, Lord Howe Warbler are just three of the twenty-four bird species which became extinct following European settlement. The demise of the Lord Howe Warbler by 1920 is attributed directly to the introduction of black rats from the SS Makambo after grounding on Lord Howe Island in 1918.

Despite the sad irreversibility of these losses, infinitely more challenging to Australia’s sensitive balance are the species the disruptor has unkindly added to the mainland’s own unique collection.

In a previous blog I discussed the introduction of the camel, which is now here to stay and firmly feral. One million of the ravenous humped beasts in Australia by 2008. After a cull, numbers were reduced to an estimated 300 000, yet still continue to grow by around 10% a year. So the high population of a decade ago is unlikely to remain a hump in the graph for long. By 2016 their numbers were already estimated to be back up to 750 000. Remarkably Australia now has the largest population of camels in the world. A mass which empties water holes and munches trees and grasses to destruction. On ranches, an estimated 80% of maintenance costs are attributed to camel damage of fences, water tanks and machinery.

However the number of camels having a wild time in sunny Australia (when they’re not evading the cullers) is a power of 10 smaller than that of the feral pig, or ‘razorback’ population. Official estimates suggest there are now 23 million feral pigs in Australia, so outnumbering the continent’s human population of 21 million. These wild hogs are descendants of those domestic porkies which early explorers released as a living larder for future expeditions. The beasts found food aplenty, an agreeable climate and no natural predators aside from the occasional ‘salty’ and piglet-pinching dingo. As a consequence they’ve grown bigger and tougher than their domestic ancestors, weighing in at up to 150kg, with fierce tusks capable of goring any passing Aussie to death. It seems if you aren’t already on the world’s most lethal species list, a short stay in the antipodes will soon get you there. And given their abundance, if you’re wondering why roast razorback isn’t by now an Aussie barbie staple, to diminish the beasts’ popularity even further, their meat is not fit for human consumption due to worm infestation and disease. What delightful, irresistible creatures.

Most people will be familiar with Australia’s ongoing rabbit problem, precipitated by the arrival of the first furry buck and doe in 1787, alongside the (no doubt) equally furry convicts, civilians and sailors of the British First Fleet. By the early 20th Century, the scale of the country’s accelerating leporine challenge necessitated the 2000 mile Western Australia rabbit fence, and was truly hammered home with the deliberate introduction of the lethal myxomatosis virus in the early 1950s. The latter inducing a slow protracted bunny death through deep skin tumours and in some cases blindness, before giving up to fatigue and disease. ‘Bright eyes, burning like fire‘.

However not so well known are the significant ecological problems caused by the shipping of another of our popular household pets – the pampered pussycat. In Australia today, there are estimated to be 2.7 million domestic cats enjoying life in suburban homes and no doubt, securing their share of the family ‘barbie’. These privileged few, with those endearing pussycat names such as Max and Molly, are unlikely to venture far from the back garden due to the now ubiquitous Aussie wild cat, of which there are estimated to be over 18 million at large on the mainland. These feral descendants are reputed to be killing almost one million birds a day and most notably, responsible for the extinction of the beautiful paradise parrot. On the plus side, should a positive be sought, due to their numbers and appetite, wild Maxes and Mollys are enthusiastically doing their bit to slow the continued rabbit explosion. Australia’s ecosystem is changing and finding new rules and players.

It’s not only released alien creatures that are threatening the new land’s natural balance. When buffel grass was introduced from Africa for grazing livestock, it had all the characteristics required of pasture for the challenging Australian conditions. In particular its rapid growth and ability to thrive in a hot, arid climate. Unfortunately that growth is now pretty much out of control, dominating entire regions to the exclusion of other species and threatening biodiversity. Furthermore with buffel grass extending across natural fire breaks, trees which would previously have survived the normal cycle of bushfire are being burnt out, together with their connected, symbiotic wildlife.

Now for the tricky bit. The matter I don’t feel I can blog about my travels in wonderful Australia without confronting. That difficult piece I want to get right. The topic that, until the National Apology of 2008, was Australia’s ‘elephant in the room’. For over 40000 years the five hundred or so different aboriginal ‘nations’, many with their own distinct language and practices, enjoyed life in this bountiful country. Their numbers were never sufficiently high, nor their technologies sufficiently developed to pose the slightest threat to the natural balance of this massive island. When the first Europeans arrived it is estimated there were at most one million indigenous inhabitants. That population is now around 650 000, just 3% of the total population of Australia. To put it mildly, the long-established aboriginal peoples have not thrived in the Australia shaped and named by those aliens who first landed just over 200 years ago. A new ‘Australia’ with not only alien ways, but alien creatures, crops and ecology.

Nowhere is the hapless plight of many of that indigenous population more stark than in the parks and malls of downtown Darwin. Wretched, disheveled groups sit in shade, lacking purpose, mostly bickering and occasionally fighting with one another. Close by, an empty grog bottle or two is never difficult to spot, discarded in the dusty Darwin dirt. A fractious cast playing out a repetitive daily tragedy, in the midst of an alien community fixed on its own busy alien routines. Two distinct populations each living out their day as if the other were invisible. Mutually alien cultures existing in the same place and time, but as if in a parallel universe.

When my daughter Francesca first arrived to work in Darwin she described, via WhatsApp, how upsetting she found the situation of the indigenous groups on the city’s streets. The conditions that most were living in and the way in which they appeared shunned or ignored by all other ethnic groups. However on visiting her in Darwin six months later, she explained how what she now found significantly more upsetting, was the realisation that in such a short time living and working in the city, she herself had stopped noticing ‘them’. And yet Francesca rides unicorns.

At national and local government level, much is now being done (albeit belatedly) to engage the indigenous peoples as stakeholders in the future of their ‘new’ country, and to recognise their contribution to the culture of the ‘old’. However, whether those two ‘countries’ are so alien to one another that it’s impossible to bridge the divide, time will tell. That clock is ticking fast. Until then the parallel universe default is likely to stay – whilst one is slowly emptied of its occupants and required no more.

Meanwhile, somewhere in another parallel universe, locked in space-time, a skinny flying kid is still chasing dreams.

The concept of space-time is both scientifically and spiritually appealing. All that has ever happened anywhere and at any time still ‘exists’, fixed in time and space and laid out on one continuous four dimensional carpet. The good and the bad. The boy in the maroon tracky can forever be observed scoring that last minute winner by simply looking from the right place. Occupying a considerably larger piece of space-time carpet than both the infatuated flying kid and tracky boy, is the land that isn’t yet Australia. Long before the alien arrival under that ‘radiant southern cross’, species evolved and some became extinct. The latter included the magnificent meiolania – a horned tortoise the size of a small car.

Without digressing too far, let me just tell you this. Tortoises are simply land-dwelling turtles. They have evolved from the same family (order Testudines). I’m personally fascinated by turtles and their lifecycle, the depth of which is another dedicated blog. However, before my adrenaline pulsing days as the flying kid or Pokemon style evolution to tracky boy, I was the stubborn non–swimming son. My father and I would fight a weekly battle. Early each Sunday morning, on his own precious day of rest, he’d wake me to cycle together to the local baths where he would endeavour to teach me to swim. The swimming baths in question were just outside our home city of York, and as was common at the time, were outdoor and unheated. Not favourable conditions to a refusenik seven year old for whom ‘aquanaut’ did not feature in his under-developed list of life goals. Had the Terrible Ten been a cool gang of pearl diving kids off Western Australia then things may have turned out different, and much easier for my sorely tested father. However our weekly unedifying performance would go like this, give or take the odd expletive. Both wearing early 1960s comedic ‘cozzies’ we approach the poolside, shivering only slightly more in February than in July. Father enters the water whilst I wait for him to diminish himself once more with his weekly lie. A process which allows me to assess the standard of today’s method acting and his level of commitment. Yes he could suppress his body shiver whilst allowing himself enough air to utter the predictable untruth ‘come on, get in, it’s not bad today – I’m warming up already’. Meanwhile I remain firmly glued to the poolside while he repeats his instruction, until the game is given away when his lips once more display that hint of blue and his nose a deeper shade of red. The signal that, not only is he now really cold, but things are about to blow. So time to release some pressure, by feigning to sit at the poolside in readiness for entry. ‘Oh no I need a wee Dad’. It’s the thought of cold water that does it you know – at this very point every week. So I trot off to the urinals and endure their familiar nauseating smell as long as possible to max out Dad’s time in the cold water and if I’m lucky, for him to start to get the excruciating ‘shin pain’. When I suspect he’s moving to poolside to extricate himself I skip back. ‘That’s better – massive queue Dad’ – always is this time on a Sunday. So now I have to demonstrate compliance by moving quickly to sitting position, with toes given the occasional tentative poke under the water’s surface film. Through uncontrollably chattering teeth I mutter ‘It’s fffffreezing’ whilst simultaneously producing the slimiest nostrils and upper lip. Subliminal – you’ll be in bother with mum if I can’t go to school tomorrow with a cold. Slowly, slowly maintain the challenge whilst managing the pressure.

After further repeated paternal instructions to ‘get in’, each a tad more insistent than the last, you sense another tipping point is about to be reached, and so at the optimum split second slip into the water. Obviously accompanied by dramatic yelps, convulsions and my now perfected ‘electrocuted frog’ impression. The latter being particularly effective as it allows you to appear to have swallowed much of the pool, and use your subsequent wrenching to plant the seed that – you’ll be in trouble with mum if I can’t go to school tomorrow with diarrhoea. Just one more subconscious nudge. And so it would continue, Instructor Dad moves his arms with feet on floor, I move my shaking arms with feet on floor. Dad moves his arms and legs, I move my arms and sink. ‘No, move your legs like this’ he’ll extol, demonstrating one more time. ‘No you’re not watching, this time watch’. He does it again and I begin to see light at the end of the tunnel. It usually starts to kick in about now. He’s getting a touch out of breath and starting to tire. Shouldn’t be long now. Two or three more extended demonstrations and it’s time to lift the feet and let the crazy frog takeover. First it’s a repeat of the attention grabbing electrocution scene, but this time on full volume. Whilst familiar to my resilient father, this act never fails to disturb onlooking parents and especially their sensitive and most precious under-fives. Fragile early pool confidence about to be crushed. Then it’s a switch to the suddenly silent – still – drowning frog. A reliable crowd stopper. I was never sure whether frogs and other amphibians could drown, but no one ever seemed to stop to think it through. I’d stay under as long as I possibly could, just leaving enough breath to launch myself up through the surface, my startling coughs and chokes accompanied, when I got the timing spot on, by shrieks and cries of younger children splashing frantically to cling on to their mums or dads and never again let go. The more the better. At this point my dad would give up, exhausted by the experience and finding himself once again unwelcome in the pool. Mission accomplished I’d joyously dry off and change for the silent cycle home. Back to a gloriously warming and well-earned Sunday dinner, head kept low for the duration, and then do my own stuff while Dad fell asleep in his armchair. Ready for another week.

So back to the turtle and the tortoise. Baby turtles in their thousands hatch from their eggs at almost the same time on the beach where they’ve been buried by their mums. All as one then scuttle frantically and clumsily towards the moonlight above the breaking sea. What if on just a few of these occasions, amongst those thousands of hatchlings was just one stubborn non-swimming son (or daughter). Refusenik young turtles. The awkward ones that said ‘No I don’t fancy that’. ‘Looks cold, wet and rough to me. Think I’ll take my chances out here. Do my own stuff’. And maybe they did, and maybe their dads weren’t happy about it, and some survived to find their Sunday dinner elsewhere. And just maybe that awkward kid, that refusenik turtle, became the first tortoise. And he met a like-minded refusenik girl turtle. They have great times together, running about beaches, getting into scrapes avoiding malicious seagulls, not going home for tea, becoming soul mates and, most crucially not growing out of each other. They just do their own stuff and become Adam & Eve to a species of tortoise. What a great a story that would be. Requiring a scientific re-examination of Darwin’s theory of evolution. It wasn’t always the advantageous mutations that did it, in some cases it was just the awkward kid who wanted to do his or her own stuff – and spotted an opportunity. Maybe that would precipitate a search for ‘the refusenik gene‘. If only space-time could show me that!

Meanwhile in that vast region of space-time which holds the land that isn’t yet Australia, remarkable flora and fauna feed off and on one another, building this massive island’s own distinct food chain, and an extraordinary ecology finds it’s equilibrium. A unique ecosystem which includes its extensive catalogue of marsupial mammals, colourful and bizarre birds of all sizes, towering trees and an uncomfortable multitude of venomous creatures. As well as a place for 500 different indigenous ‘nations’ and cultures. While kangaroos hop and koalas snooze their way to the space-time carpet’s present day edge, the aliens are only just visible yet their impact already beginning to disturb and tear at nature’s deepest roots. The inescapable space-time carpet will hold on permanent record their long-term impact – whether that be a progressive disruption or ecological destruction. Observable for all eternity by those in a position to see. Be they aliens at home or afar.

Our land abounds in nature’s gifts

Of beauty rich and rare;

In history’s page, let every stage Advance Australia Fair.

Such responsibility.